Biography Of Kahlil Gibran

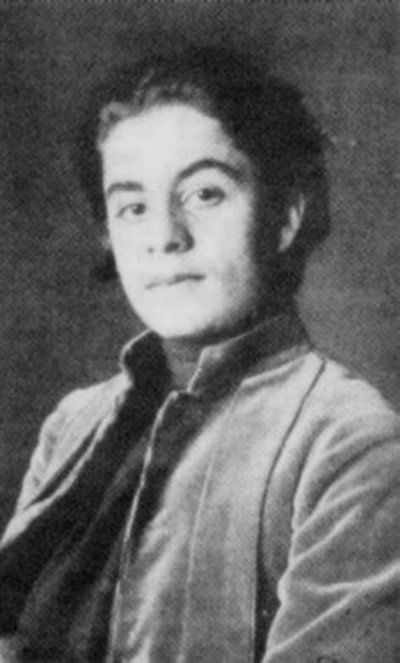

Gibran Khalil Gibran was born in Bisharri, Lebanon on 6 January 1883. At the age of twelve he emigrated with his mother, halfbrother and two younger sisters to the United States, where his first name was dropped and the spelling of ‘Khalil’ was changed to ‘Kahlil’ to suit American pronunciation. Once the family had settled in Boston, he returned to Lebanon for two years to study, and for a brief visit four years later in 1902, but otherwise never saw his native land again. Of the four members of his family in Boston, three fell untimely victims to tuberculosis; only Mariana, his first sister, survived beyond 1903 and would eventually outlive Kahlil himself.

While at school, Gibran developed a keen interest in literature and showed a flair for painting and drawing. At the age of twenty-two, his artistic talents were recognized by Fred Holland Day, a well-known Boston photographer, who organized an exhibition of his paintings. Another exhibition followed at the Cambridge School, whose owner and headmistress, Mary Haskell, subsequently became Gibran’s confidante, patron and benefactor.[1]

Biography Of Kahlil Gibran. Up to this point Gibran’s writings had been little more than sketches, some of which provided material for later works. As yet not completely fluent in the English language, he began writing for an Arabic newspaper in Boston, and in 1905 his first book, Al-Musiqah (Music), was published. This was followed by ‘Ara’is al-Muruj (Nymphs of the Valley), in which he was fiercely critical of Church and State. He became known as something of a rebel, a reputation he confirmed with Al-Arwah al-Mutamarridah (Spirits Rebellious) in 1908.

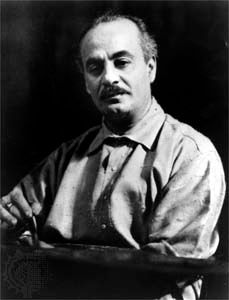

The next two years were spent as a student at the Académie Julien and the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, thanks to the generous sponsorship of Mary Haskell. In Paris he met the sculptor Auguste Rodin, who is said to have compared Gibran’s work to that of William Blake – Gibran’s fellow visionary in mode of thought, views on Church and State, grace of spirit and artistic style. Gibran’s subsequent paintings and drawings contain many echoes of both Blake and Rodin, and Blake’s influence pervades his writings.

Whilst in Paris he sketched portraits of a number of eminent people, including Rodin himself, the composer Claude Debussy, the actress Sarah Bernhardt and the poet W.B. Yeats. A particularly indelible impression was left on Gibran by another who sat for him while visiting the United States: Abdul Baha, son of the founder of the Baha’ي Faith. Abdul Baha’s message celebrated the power and efficacy of an all-embracing unity. He emphasized the need to reconcile opposites, create harmony, and recognize the complementary values of each entity. It was this vision of unity in diversity that captured Gibran’s thinking and philosophy. The influence of Abdul Baha on Gibran has been estimated in Susan Reynolds’ interesting paper in which she states:

Gibran said of Abdul Baha, ‘For the first time I saw form noble enough to be a receptacle for the Holy Spirit’;[3] and years later Gibran stated that Abdul Baha had provided a model for his Jesus, the Son of Man.[4] On his return to Boston, Gibran proposed marriage to Mary Haskell, who was ten years his senior. She declined the offer, but remained his lifelong friend and collaborator.

Biography Of Kahlil Gibran. In 1912, Gibran moved to New York on the advice of his friend and fellow Lebanese émigré writer Ameen Rihani, and rented a studio which he called ‘The Hermitage’. The same year saw the publication of his Al-Ajninal al-Mutakassirah (The Broken Wings), a semi-autobiographical tale of unrequited passion.

Dam’ah wa’Ibtisamah (A Tear and a Smile), a collection of prose poems, followed in 1914. Around this time Gibran began corresponding with May Ziadah, a young Lebanese writer living in Egypt, and over the next twenty years they formed a unique relationship, a love affair that took place entirely in their letters to one another, without their ever meeting.[5]

During the war years Gibran consolidated his knowledge of English, and by 1918 he was sufficiently fluent in the language of his adopted country to write and publish his first book in English. This was The Madman, a collection of Sufi style parables. Two other Arabic works, Al-Mawakib (The Procession) and the powerful Al-‘Awasif (The Tempests), as well as Twenty Drawings, a collection of his artwork with an introduction by Alice Raphael, preceded the publication of his second book in English, The Forerunner, its form being similar to that of The Madman. Soon afterwards Gibran and a group of fellow Arab émigré writers formed Arrabitah (the Pen Bond), a literary society that exerted a crucial shaping influence on the renaissance of Arabic literature in the United States. Among the founders was the distinguished Lebanese writer Mikhail Naimy, by now one of Gibran’s closest friends.[6]

The yearning for wahdat al-wudjud (unity of being) – the Sufi concept with which The Prophet is infused – was encapsulated in Gibran’s only play and last major Arabic work, Iram Dhat al-‘Imad (Iram, City of Lofty Pillars). Published in 1921, it was a worthy precursor to The Prophet and incorporates many of the metaphors that Gibran was to use so successfully in the latter.[7] A smaller Arabic work, Al-Badayi’ wa’l-Tarayif (Beautiful and Rare Sayings), followed in 1923, but this was completely overshadowed by the publication in the same year of his third book in English, The Prophet.

The success of The Prophet was unprecedented and won him universal recognition and acclaim; in America it outsold all other books in the twentieth century except the Bible, a major influence on its style and thought.

Biography Of Kahlil Gibran. After the success of The Prophet, Gibran’s health greatly deteriorated, but he managed to complete another four books in English: Sand and Foam (1926), The Earth Gods (1931), The Wanderer (published posthumously in 1932), and the finest of his late works, Jesus, the Son of Man (1928), a highly original collection of stories about Christ. Gibran died on 10 April 1931, at the age of just forty-eight, the cause of death being diagnosed as cirrhosis of the liver. His body was taken back to Lebanon and buried in a special tomb in Bisharri. An unfinished work called The Garden of the Prophet, which he intended as one of two sequels to The Prophet, was completed and published in 1933 by his companion and self-proclaimed disciple and publicist, Barbara Young.

Biography Of Kahlil Gibran. Footnote:

While at school, Gibran developed a keen interest in literature and showed a flair for painting and drawing. At the age of twenty-two, his artistic talents were recognized by Fred Holland Day, a well-known Boston photographer, who organized an exhibition of his paintings. Another exhibition followed at the Cambridge School, whose owner and headmistress, Mary Haskell, subsequently became Gibran’s confidante, patron and benefactor.[1]

Biography Of Kahlil Gibran. Up to this point Gibran’s writings had been little more than sketches, some of which provided material for later works. As yet not completely fluent in the English language, he began writing for an Arabic newspaper in Boston, and in 1905 his first book, Al-Musiqah (Music), was published. This was followed by ‘Ara’is al-Muruj (Nymphs of the Valley), in which he was fiercely critical of Church and State. He became known as something of a rebel, a reputation he confirmed with Al-Arwah al-Mutamarridah (Spirits Rebellious) in 1908.

The next two years were spent as a student at the Académie Julien and the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, thanks to the generous sponsorship of Mary Haskell. In Paris he met the sculptor Auguste Rodin, who is said to have compared Gibran’s work to that of William Blake – Gibran’s fellow visionary in mode of thought, views on Church and State, grace of spirit and artistic style. Gibran’s subsequent paintings and drawings contain many echoes of both Blake and Rodin, and Blake’s influence pervades his writings.

Whilst in Paris he sketched portraits of a number of eminent people, including Rodin himself, the composer Claude Debussy, the actress Sarah Bernhardt and the poet W.B. Yeats. A particularly indelible impression was left on Gibran by another who sat for him while visiting the United States: Abdul Baha, son of the founder of the Baha’ي Faith. Abdul Baha’s message celebrated the power and efficacy of an all-embracing unity. He emphasized the need to reconcile opposites, create harmony, and recognize the complementary values of each entity. It was this vision of unity in diversity that captured Gibran’s thinking and philosophy. The influence of Abdul Baha on Gibran has been estimated in Susan Reynolds’ interesting paper in which she states:

'Alongside the influence of the writers and philosophers from whom Gibran drew insight and inspiration, there was another and equally significant one without which neither The Prophet (1923) nor Jesus, the Son of Man (1928) could have been written – certainly not in the form in which we now have them. It proceeded from yet another in the series of distinguished figures whom Gibran immortalized in a portrait, and perhaps the greatest of them all:`Abdu’l-Baha.'[2]

Gibran said of Abdul Baha, ‘For the first time I saw form noble enough to be a receptacle for the Holy Spirit’;[3] and years later Gibran stated that Abdul Baha had provided a model for his Jesus, the Son of Man.[4] On his return to Boston, Gibran proposed marriage to Mary Haskell, who was ten years his senior. She declined the offer, but remained his lifelong friend and collaborator.

Biography Of Kahlil Gibran. In 1912, Gibran moved to New York on the advice of his friend and fellow Lebanese émigré writer Ameen Rihani, and rented a studio which he called ‘The Hermitage’. The same year saw the publication of his Al-Ajninal al-Mutakassirah (The Broken Wings), a semi-autobiographical tale of unrequited passion.

Dam’ah wa’Ibtisamah (A Tear and a Smile), a collection of prose poems, followed in 1914. Around this time Gibran began corresponding with May Ziadah, a young Lebanese writer living in Egypt, and over the next twenty years they formed a unique relationship, a love affair that took place entirely in their letters to one another, without their ever meeting.[5]

During the war years Gibran consolidated his knowledge of English, and by 1918 he was sufficiently fluent in the language of his adopted country to write and publish his first book in English. This was The Madman, a collection of Sufi style parables. Two other Arabic works, Al-Mawakib (The Procession) and the powerful Al-‘Awasif (The Tempests), as well as Twenty Drawings, a collection of his artwork with an introduction by Alice Raphael, preceded the publication of his second book in English, The Forerunner, its form being similar to that of The Madman. Soon afterwards Gibran and a group of fellow Arab émigré writers formed Arrabitah (the Pen Bond), a literary society that exerted a crucial shaping influence on the renaissance of Arabic literature in the United States. Among the founders was the distinguished Lebanese writer Mikhail Naimy, by now one of Gibran’s closest friends.[6]

The yearning for wahdat al-wudjud (unity of being) – the Sufi concept with which The Prophet is infused – was encapsulated in Gibran’s only play and last major Arabic work, Iram Dhat al-‘Imad (Iram, City of Lofty Pillars). Published in 1921, it was a worthy precursor to The Prophet and incorporates many of the metaphors that Gibran was to use so successfully in the latter.[7] A smaller Arabic work, Al-Badayi’ wa’l-Tarayif (Beautiful and Rare Sayings), followed in 1923, but this was completely overshadowed by the publication in the same year of his third book in English, The Prophet.

The success of The Prophet was unprecedented and won him universal recognition and acclaim; in America it outsold all other books in the twentieth century except the Bible, a major influence on its style and thought.

Biography Of Kahlil Gibran. After the success of The Prophet, Gibran’s health greatly deteriorated, but he managed to complete another four books in English: Sand and Foam (1926), The Earth Gods (1931), The Wanderer (published posthumously in 1932), and the finest of his late works, Jesus, the Son of Man (1928), a highly original collection of stories about Christ. Gibran died on 10 April 1931, at the age of just forty-eight, the cause of death being diagnosed as cirrhosis of the liver. His body was taken back to Lebanon and buried in a special tomb in Bisharri. An unfinished work called The Garden of the Prophet, which he intended as one of two sequels to The Prophet, was completed and published in 1933 by his companion and self-proclaimed disciple and publicist, Barbara Young.

A new annotated edition

introduced and edited by

Suheil Bushrui

www. oneworld-publications .com

introduced and edited by

Suheil Bushrui

www. oneworld-publications .com

Biography Of Kahlil Gibran. Footnote:

[1] The relationship between Gibran and Mary Haskell is exceptionally well documented in two overlapping but by no means identical books (Hilu 1972 and Otto 1963). These two books are based on the correspondence between Kahlil Gibran and Mary Haskell, and Mary Haskell’s memoirs as recorded in her journal.

[2] Reynolds 2012. See also Bushrui and Jenkins 1998, pp. 9, 252–255.

[3] Honnol 1982, p. 158.

[4] Gail 1982, p. 228.

[5] A number of Gibran’s letters to May containing vivid and richly lyrical passages that rank alongside the best of his writing in Arabic have been published in a volume of English translations, Gibran: Love Letters (Bushrui and al-Kuzbari, 1995).

[6] Naimy was one of Gibran’s earliest biographers in Arabic and subsequently made his own translation of the book into English (see Naimy 1967). Though not factually reliable, it represents a fascinating insight into the mind and Arabian character of Gibran.

[7] For further details of Iram, City of Lofty Pillars, its dealings with the Sufi concept of wahdat al-wudjud (unity of being) and its relationship to The Prophet, see Bushrui and Jenkins 1998, pp. 212–216.

[2] Reynolds 2012. See also Bushrui and Jenkins 1998, pp. 9, 252–255.

[3] Honnol 1982, p. 158.

[4] Gail 1982, p. 228.

[5] A number of Gibran’s letters to May containing vivid and richly lyrical passages that rank alongside the best of his writing in Arabic have been published in a volume of English translations, Gibran: Love Letters (Bushrui and al-Kuzbari, 1995).

[6] Naimy was one of Gibran’s earliest biographers in Arabic and subsequently made his own translation of the book into English (see Naimy 1967). Though not factually reliable, it represents a fascinating insight into the mind and Arabian character of Gibran.

[7] For further details of Iram, City of Lofty Pillars, its dealings with the Sufi concept of wahdat al-wudjud (unity of being) and its relationship to The Prophet, see Bushrui and Jenkins 1998, pp. 212–216.

0 komentar:

Post a Comment